Russia places its hopes on fossil fuels

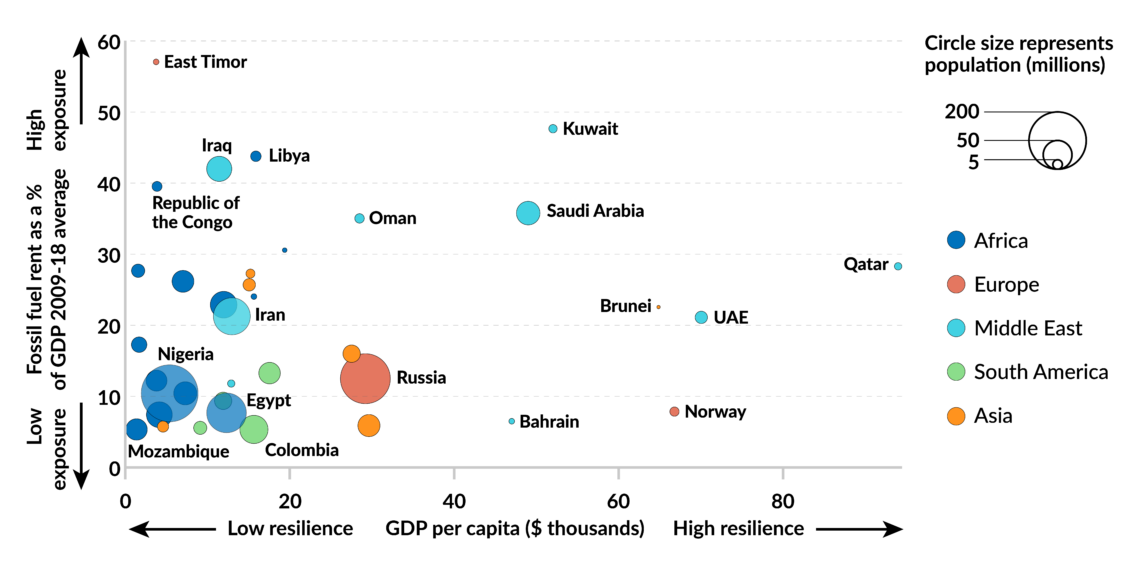

Russia is the world’s largest exporter of fossil fuels. Accelerating decarbonization worldwide could threaten Moscow’s energy superpower status in the long run, potentially destabilizing the Putin regime and its symbiotic relationship with the oil and gas industry.

In a nutshell

- Russia wants to increase its production of fossil fuels

- However, its oil and gas exports will become less profitable

- Moscow is unlikely to seriously pursue a green transition

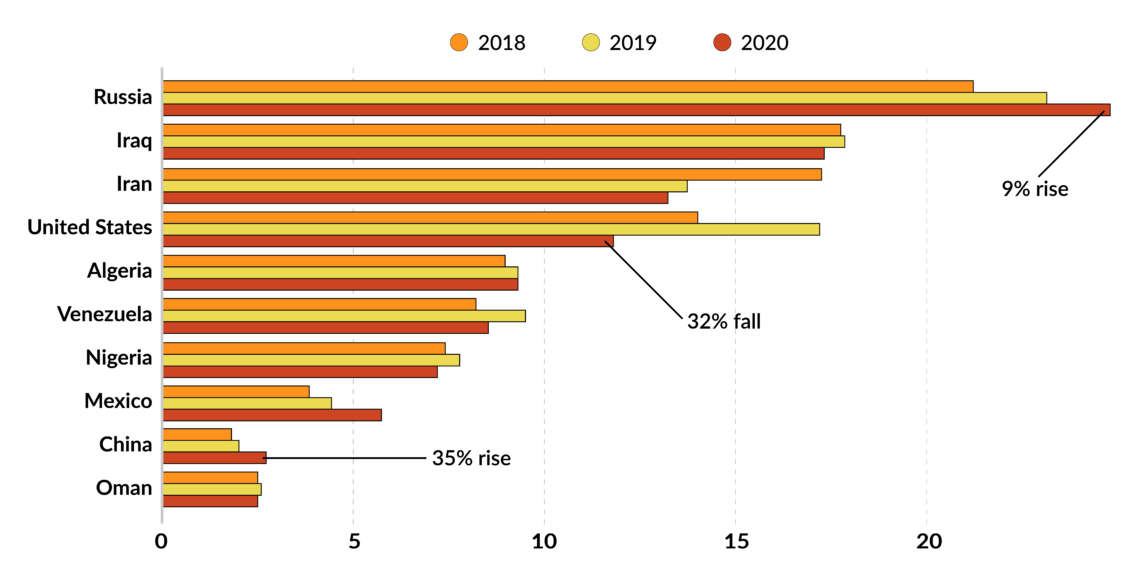

Russia’s energy sector has muddled through the difficult times of the Covid-19 pandemic. The OPEC+ production cuts have stabilized global oil prices above Russia’s budgetary break-even price of around $42 per barrel. Oil and gas still make up about 40 percent of its federal state budget revenue and more than 50 percent of export revenue.

International gas prices have increased since the end of last year, despite the global oversupply. However, higher gas prices in Europe could prove temporary. Russia’s total gas exports to the continent fell from around 199 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 2019 to some 175 bcm in 2020, with only 167 bcm projected for 2021 due to intense competition and oversupply on global markets.

Old fuels

While Europe and China have adopted plans to decarbonize, Russia’s new “Energy Strategy to 2035” (ES-2035), published in March 2020, focuses almost exclusively on maintaining its struggling oil production and on increasing gas and coal exports over the next 15 years. Coal accounts for 14 percent of Russia’s energy mix, and exports are expected to remain the fifth-largest source of revenue for the state budget, at about $17 billion per year. Russia could become the world’s largest coal exporter if its share of global trade grows from 11 to 25 percent by 2035 as planned.

Russia’s new ‘Energy Strategy to 2035’ fails to take into account several new developments.

By 2035, Russia also hopes to expand its liquefied natural gas (LNG) export capacity from 27 million ton per year (mt/y) to 140 mt/y, as well as to increase its market share from 8 to 20-25 percent. Its total gas exports are projected to increase by another 30 percent despite the competing supply of inexpensive LNG from the United States and the Middle East. Moscow also plans a second gas pipeline to China, Power of Siberia-2, that would reach a capacity of 50 bcm per year after 2030, complementing Power of Siberia-1, which has a capacity of 38 bcm per year.

New strategy

The ES-2035 does not foresee a major role for nonfossil fuels beyond nuclear power (19 percent of Russia’s energy mix) and hydropower (18 percent). In 2020, Russia had just 0.1 gigawatts (GW) of wind and 1.1 GW of solar power in its total electricity generation (253 GW). In contrast to China, the country is not actively involved in developing clean energy technologies like batteries or electric vehicles. Its new strategy envisions renewables to reach only 4 percent of the energy mix by 2035. The Kremlin perceives green energy as a potential threat rather than an opportunity.

The ES-2035 also fails to take into account several new policy and market developments. By building Nord Stream 2 and two TurkStream gas pipelines, Russia will have the capacity to export more than 300 bcm to Europe. Its current European gas exports are only slightly over half of its total capacity.

The EU’s new European Green Deal (EGD) and its legally binding emission reduction target of 55 percent will profoundly affect member states’ energy mix, policy and legislation. Although natural gas has been considered a transition fuel for decarbonization, the European Commission wants to phase out conventional gas after 2030 and replace it with hydrogen, methane, and other green gases to achieve its climate objectives by 2050.

Facts & figures

New market analyses predict that, like coal, global oil consumption could peak between 2025 and 2030 rather than after. Before 2020, it was forecast that natural gas would be the only fossil fuel to experience substantial growth, with a projected 45 percent increase. China and the U.S. have also adopted new energy policies to accelerate their decarbonization. Solar and wind energy, as well as battery storage adoption, have made renewables some of the cheapest options in the U.S. power market. New forecasts have projected that they will be cost-competitive with coal and gas by 2023 or 2024. Bloomberg has warned that “gas is the new coal,” potentially resulting in 100 billion in assets being stranded in the U.S.

The melting of permafrost, which covers 66 percent of Russia’s landmass, could also pose a challenge. The Kremlin hopes to profit from access to the Arctic, which holds 25 percent of its oil and 72 percent of its gas reserves, and from the opening of a northern Arctic sea route from Europe to Asia. But President Vladimir Putin, who has repeatedly denied that human activity plays a role in global warming, admitted in the summer of 2020 that the Russian permafrost region was warming two and a half times faster than the world average temperature. That is an expensive turn of events for Russia: existing infrastructure needs to be stabilized and rebuilt. In recent years, a tank broke and spilled 21,000 tons of diesel into a Siberian river, roads and pipelines collapsed, and forest fires broke out, threatening the massive investments for new oil and gas fields in the region. Although the government approved a “National Climate Adaptation Plan” in December 2019, Russian experts have also dismissed any new policies given Russia’s economic and geopolitical priorities.

Forecasts and challenges

With the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, Russia has been one of the world’s three largest oil producers during the last decade. It also has the world’s largest gas reserves and the seventh-largest oil reserves. Its relatively low debt and high foreign currency reserves will allow the country to continue relying on fossil fuels production and exports for some time. EU gas import demand is projected to keep increasing until 2030, because while its demand for the fuel is expected to remain stable until then, its production will continue to decline. Today, around 72 percent of EU gas is imported and this could increase to more than 80 percent by 2030.

In 2020, Russian pipeline supplies made up 43 percent of the EU’s total net gas imports, despite decreasing from 358 bcm in 2019 to 326 bcm. In the fourth quarter of 2020, Russia’s share of combined pipeline and LNG imports in the EU further increased to 53 percent (49 percent pipeline and 4 percent LNG) according to the latest statistics.

The elimination of gas in power generation appears to have already begun in Europe.

Russia was able to replace the failing South Stream gas pipeline with TurkStream, whose first line became operational in January 2020 with a capacity of 15.75 bcm per year. A second one is scheduled to begin operation in 2021 and will completely replace the Trans-Balkan pipeline, which goes through Ukraine. But like Nord Stream 2, TurkStream is subject to U.S. sanctions, raising doubts over its completion. The Kremlin has also paved the way for Novatek and Rosneft to increase their LNG exports to Europe.

Russian oil production requires an average price of about $35 per barrel after tax to be profitable. The production costs of Russia’s aging oil fields are generally higher than in the Middle East. The development of new Russian oil fields is expensive and requires Western technologies and higher oil prices. No new oil project has been commissioned in the Arctic, where the break-even price is $100 per barrel. At the current price level, only a third of Russia’s proven reserves will be profitable to extract. The country’s oil production may already have peaked. The ES-2035 foresees a 30 percent decline by 2035. If global oil demand is to peak between 2025 and 2030 rather than after 2030 as projected post-Covid, any new Arctic oil and LNG production would become riskier and less profitable.

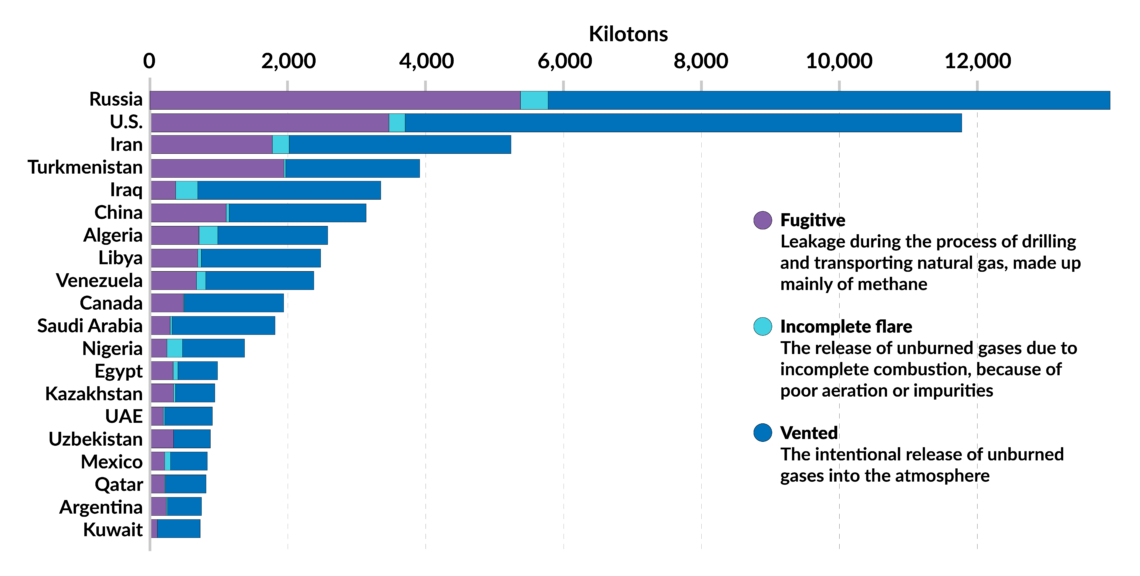

Russia is also the largest source of methane leaks and gas flaring. The carbon footprint resulting from these practices will also threaten the international competitiveness of natural gas compared to renewables and more efficient industries.

Facts & figures

Europe in transition

Before Covid-19, the EU’s natural gas forecasts already predicted stagnating gas demand until 2030 and a continuous decrease thereafter. In 2020, the Union’s natural gas consumption declined to 394 bcm from 406 bcm in 2019. Domestic gas production fell from 70 bcm/y to 54 bcm/y. Total net gas imports sank from 358 bcm in 2019 to 326 bcm in 2020. Total EU LNG imports amounted to 84 bcm/y compared with 88 bcm in 2019.

To meet the goals of the EGD, the European Commission has determined that the EU’s fossil fuel consumption needs to decrease by 36 percent from 2020 to 2030. Coal imports are expected to fall by 55 to 71 percent from their 2015 level, oil imports by 23 to 25 percent and natural gas imports by at least 13 percent.

On paper, Russia has plans to enhance its energy efficiency.

For the first time, the role of natural gas as a clean energy source has come under question, meaning it could no longer be eligible for EU financing. On April 18, 2021, the European Commission once again postponed its decision on whether to classify natural gas as green energy. The carbon price within the EU’s Emission Trading System (ETS) has risen to a record of 50 euros per ton, causing additional uncertainties for the European gas industry. In 2020, gas power plants overtook lignite as the Union’s largest source of emissions in the power sector, due to the coal phaseout and high carbon prices.

The gradual elimination of gas in power generation appears to have already begun in Europe. Wary investors are turning away from gas at an even faster pace than they did with coal. European companies are struggling to sell gas power plants. At present price levels, coal-fired energy generation is highly unprofitable, and gas appears to be following the same path. Renewables and battery storage solutions are improving and becoming cheaper. Moreover, the EU plans to introduce a border tax that would further lower the profitability of Russian fossil fuel exports to Europe.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

Russia is the 11th-largest economy in the world, but its share of global domestic product has been halved over the last decade. Since regime change appears improbable in the next two decades, a slow but steady economic decline appears to be the most likely development. While the Western world and – to some extent – China are moving away from fossil fuels, the medium-term energy strategy focuses on keeping its oil industry afloat and increasing gas and coal exports.

A continued rise in coal exports has been described as unrealistic by Russian energy experts, but gas production could still increase in the next decade due to growing demand in Asia. However, profits will decrease as gas prices drop and global demand slows because of oversupply. New pipeline projects like Nord Stream 2 and TurkStream are also unlikely to be profitable. They will not be able to operate at full capacity after 2030 unless they begin to transport blue hydrogen (derived from natural gas using carbon capture and storage).

On paper, Russia has plans to enhance its energy efficiency by using carbon capture and storage and developing blue and turquoise hydrogen (derived from natural gas using methane pyrolysis). But the Kremlin’s green intentions should be viewed with some skepticism, as past experiences suggest. One of Russia’s foremost energy experts, Konstantin Simonov, director general of the National Energy Security Fund, warned at the end of April: "Russia has no money in its coffers to pursue green energy, nor would such a course be a moneymaker. However rosy a picture the proponents of a green energy transition in Russia might paint, it could never generate export revenue comparable to that of oil and gas... As disappointing as it might sound, any honest observer can see that Russia’s green policy is simply another struggle for government funds and not for a better environment."